Posted on

September 30, 2020

Pittsburgh Panderers

Rooney family can't undo the past

by

Daniel

Clark

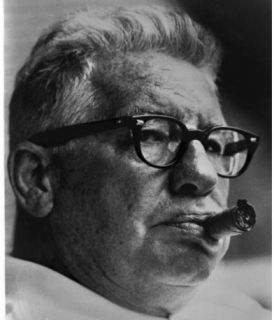

After his team won Super Bowl XLIII, Pittsburgh

Steelers owner Dan Rooney thanked President Barack Obama, in one of the most shameless

exhibitions of sycophancy in sports history.

Everybody knew at the time that he was angling for an appointment to

become U.S. Ambassador to Ireland, which he would receive six months later, but

there was more to it than that. The

episode was just one among a long-running series of conspicuous pandering

gestures on the part of the Rooney family, designed to demonstrate their

opposition to racism.

Most

famous among these efforts is the National Football League's "Rooney Rule,"

which Dan Rooney proposed while serving as chairman of the league's "diversity

committee." The rule requires a team

with a head coaching vacancy to interview at least one ethnic minority

candidate. It is not a hiring quota, and

in fact there are now the same number of black head coaches in the NFL as there

were when the rule was implemented in 2003.

All it really does is waste those candidates' time and falsely get their

hopes up.

Most

famous among these efforts is the National Football League's "Rooney Rule,"

which Dan Rooney proposed while serving as chairman of the league's "diversity

committee." The rule requires a team

with a head coaching vacancy to interview at least one ethnic minority

candidate. It is not a hiring quota, and

in fact there are now the same number of black head coaches in the NFL as there

were when the rule was implemented in 2003.

All it really does is waste those candidates' time and falsely get their

hopes up.

The Steelers' own hiring of head coach Mike Tomlin is

often cited as an example of the Rooney Rule's success, but the Rooneys themselves have refuted that impression, noting

that they had already satisfied the rule's requirements before interviewing

Tomlin. In truth, the idea that they

would have only considered a black candidate because it was required by rule is

an insult to the Rooneys, but one that they have no

compunction about directing at others.

This season, the Steelers, among many other football

teams, have launched a coercive "social justice" initiative that treats its

players -- and especially its black players -- as an unthinking monolith, devoid

of any capacity for reason. It was

decided, although there's considerable dispute over how it was decided, that the players would wear helmets emblazoned

with the name Antwon Rose Jr. Rose was a

teenager who was shot by an East Pittsburgh policeman while fleeing a

bullet-riddled car that had just been used in a drive-by shooting.

Offensive tackle Alejandro Villanueva covered up

Rose's name on his helmet with the name of a deceased war hero he thought to be

more deserving of a tribute. He was

criticized for doing so by Rose's mother, Michelle Kenney, who said he "showed

us exactly who he is," in a less than subtle suggestion of racism. After the opening game, center Maurkice Pouncey, who is black and who generously supports

police-related charities, also decided to remove the name from his helmet,

saying he had "inadvertently supported a cause of which I did not fully

comprehend the entire background of the case."

Kenney struck a more conciliatory tone with Pouncey, but cautioned, "Don't

set the movement backward because of your own personal agenda." So, the players must not let their personal

convictions interfere with compulsory exercises in groupthink.

Art

Rooney II, who assumed the role of team owner when his father Dan died in 2017,

publicly disagreed with this sentiment.

His statement began, "As an organization, we respect the decisions of

each player, coach and staff member relating to how to express themselves on

social justice topics." Sounds nice, but

if that's really Rooney policy, then why had the entire team been instructed to

endorse a single form of expression -- and a very divisive one at that -- when

there could not have been any expectation that all 53 individuals would

agree? The players were not told that

they could tape their own messages to their helmets. They were assigned Antwon Rose Jr.'s name as

a mass-produced part of their uniform.

It seems that the organization's respect for each player only kicked in

once the players began to resist.

Art

Rooney II, who assumed the role of team owner when his father Dan died in 2017,

publicly disagreed with this sentiment.

His statement began, "As an organization, we respect the decisions of

each player, coach and staff member relating to how to express themselves on

social justice topics." Sounds nice, but

if that's really Rooney policy, then why had the entire team been instructed to

endorse a single form of expression -- and a very divisive one at that -- when

there could not have been any expectation that all 53 individuals would

agree? The players were not told that

they could tape their own messages to their helmets. They were assigned Antwon Rose Jr.'s name as

a mass-produced part of their uniform.

It seems that the organization's respect for each player only kicked in

once the players began to resist.

The Rooneys' repeated,

overzealous forays into racial politics serve a purpose that is plain to see in

this era of iconoclasm. You need not

look any farther than patriarch and team founder Art Rooney Sr., a.k.a., The

Chief. The world of sports has seldom

seen anybody as widely liked and uncontroversial. For all his decades as a public figure, there

simply are no anecdotes about Rooney treating anyone badly or being unpleasant

in any way. There is, however, one

stubborn blot on his record, which is that he owned the Steelers during a time

when the NFL team owners are said to have had a "gentlemen's agreement" not to

sign any black players. There was no

written policy to this effect, and he denied that any such agreement existed,

but the circumstantial evidence is compelling.

The agreement is supposed to have lasted from 1934

until 1946. That's when the city of Los

Angeles included a nondiscrimination clause in the terms of the Rams' lease of

the Coliseum. At the same time, the

All-American Football Conference came into existence. Most teams in the AAFC had black players, and

they brought them into the NFL when the two leagues merged in 1950. From that point, the owners who had allegedly

been part of the agreement gradually abandoned it in order to remain competitive.

In 1933, there were two black players in the NFL, one

of whom was Steelers' tackle Ray Kemp.

He was not re-signed for the 1934 season, and the Steelers had no other

black players until 1952. Had there been

no agreement, what else would have kept black players out of the league, and

off the Steeler roster, for all those years?

If the black players simply weren't there, then how did the AAFC manage

to find them? Ditto that for the L.A.

Rams. For these among other reasons,

there is no serious skepticism among football historians over whether this

prohibition existed, The Chief's denials notwithstanding.

This

is not to suggest that Art Rooney Sr. was a racist. In fact, there is an abundance of evidence to

the contrary. For starters, he did not

keep black players off his team before the agreement existed. Ironically, it was because of his objection to

segregation that he was all alone among the owners in voting against the New

York Yanks' move to Dallas in 1951. Six

years later, Rooney hired Lowell Perry to coach his wide receivers, making Perry

the only black position coach in the NFL at the time. He once canceled an exhibition game in

Atlanta, rather than have his players stay in segregated hotels.

This

is not to suggest that Art Rooney Sr. was a racist. In fact, there is an abundance of evidence to

the contrary. For starters, he did not

keep black players off his team before the agreement existed. Ironically, it was because of his objection to

segregation that he was all alone among the owners in voting against the New

York Yanks' move to Dallas in 1951. Six

years later, Rooney hired Lowell Perry to coach his wide receivers, making Perry

the only black position coach in the NFL at the time. He once canceled an exhibition game in

Atlanta, rather than have his players stay in segregated hotels.

It's unimaginable that Rooney would have proposed a

thing like the "gentlemen's agreement" on his own. It's entirely plausible, even probable, that

he personally disliked and disapproved of the agreement. One thing that is known for certain, however,

is that he did not defy it. That's a fact, and no amount of embarrassing,

groveling suckuppery on the part of his progeny can

make it no longer be true.

It should go without saying that all human beings are

flawed. That doesn't mean The Chief

wasn't a great man, or that his statue ought to be uprooted from outside Heinz

Field and dumped in the river. By all

accounts, his acquiescence to the agreement was out of character, but it is a

part of his story, and it shouldn't just be wiped away.

The Rooney family cannot undo the past, because the

present simply does not provide them the opportunity. The sinister forces that The Chief was often

but not always willing to confront are no longer there for the Rooney

grandchildren and great-grandchildren to vanquish. If the systemic racism of more than a

half-century ago still existed, they would be able to specifically identify it

and propose a relevant course of action.

Instead, they're offering a lot of misguided, symbolic trifles without any

positive real-world impact. What good

they think it does is not readily apparent.

The next time someone points out the "gentlemen's agreement," bragging

about having put the name of a dead gangster on the base of the team's helmets

will be a poor retort.

The Shinbone: The

Frontier of the Free Press