Posted on March

11, 2024

Sorry, Dahlink

If Budapest is toothless, then so is

Article 5

by

Daniel

Clark

In a March 1st posting on the National Review blog

"The Corner," Michael Brendan Dougherty set his sights on an easy target in

retiring senator Mitt Romney, but misfired.

In response to a recent interview the former presidential candidate gave

to CNN, Dougherty wrote, "First problem is that [Romney] mischaracterizes the

Budapest memorandum as pledging us 'to help defend the people of Ukraine.' It does no such thing, and it cannot be

construed that way."

Okay, so the memorandum makes no mention of "the

people of Ukraine." What it does say is

that its signatories (the United States, Great Britain and Russia) "reaffirm

their commitment ... to respect the independence and sovereignty and the existing

borders of Ukraine," and that they "reaffirm their obligation to refrain from

the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political

independence of Ukraine." Romney

understands this (or construes it, if you will) to amount to a defense

of the Ukrainian people. How reasonable

is it to draw a semantic distinction, as Dougherty does, such that a

multilateral agreement to respect a nation's sovereignty and political

independence is not essentially a defense of its people?

As

long as Dougherty insists on parsing words, it must be pointed out that there

is a difference between a pledge and a commitment. A pledge is a binding promise. When Dougherty says that the Budapest

Memorandum "does not pledge military aid," he is correct, because the document

does not spell out what must be done in the event of a violation. Romney did not use the word "pledge," though. What he said was that failure to support

Ukraine "will make it very clear to people around the world that you really

can't trust America's word, because we made a commitment in 1994 to respect the

sovereignty of Ukraine, to help defend the people of Ukraine if they were

attacked." In fact, the commitment of

all three nations to respect Ukrainian sovereignty is right there in the

document.

As

long as Dougherty insists on parsing words, it must be pointed out that there

is a difference between a pledge and a commitment. A pledge is a binding promise. When Dougherty says that the Budapest

Memorandum "does not pledge military aid," he is correct, because the document

does not spell out what must be done in the event of a violation. Romney did not use the word "pledge," though. What he said was that failure to support

Ukraine "will make it very clear to people around the world that you really

can't trust America's word, because we made a commitment in 1994 to respect the

sovereignty of Ukraine, to help defend the people of Ukraine if they were

attacked." In fact, the commitment of

all three nations to respect Ukrainian sovereignty is right there in the

document.

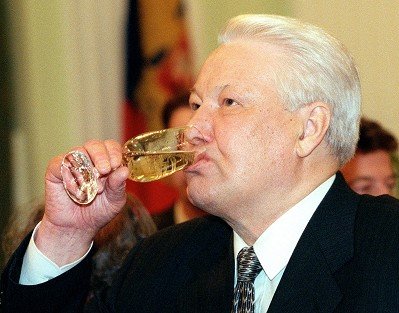

The Budapest Memorandum is not a treaty. It is an agreement that was signed by

President Bill Clinton, Prime Minister John Major and President Boris Yeltsin,

to persuade Ukraine to turn its Soviet-era nuclear weapons over to Russia,

presumably to be destroyed. Ukraine

understood that Russia had designs on conquering it, and would never have

trusted a simple promise from its government that it would not invade. The guarantee of security that convinced Ukraine

to give up its nuclear deterrent came from the United States. Nobody ever supposed that there was a need

for the U.S. and Britain to promise not to violate the territorial integrity of

Ukraine. The Ukrainians surrendered

their nukes with the understanding that the Western powers would hold Russia to

the agreement. Admittedly, the deal does

not contain a "pledge" of military aid, but our commitment could hardly be more

clear.

In

the absence of a mechanism to compel us to honor that commitment, opponents of

aid to Ukraine are taking the Animal House approach, telling the

Ukrainians in so many words that they screwed up. They trusted us. In addition to the basic immorality of that,

it would obviously become a negative factor in any negotiation our country has

with any other country in the foreseeable future. Certainly any similar attempt to contain

nuclear proliferation would be a nonstarter, after we had created the very

outcome that the Budapest Memorandum was designed to prevent. Not only that, but doubts would be cast over

all of our already existing international commitments, including those to our

NATO allies.

In

the absence of a mechanism to compel us to honor that commitment, opponents of

aid to Ukraine are taking the Animal House approach, telling the

Ukrainians in so many words that they screwed up. They trusted us. In addition to the basic immorality of that,

it would obviously become a negative factor in any negotiation our country has

with any other country in the foreseeable future. Certainly any similar attempt to contain

nuclear proliferation would be a nonstarter, after we had created the very

outcome that the Budapest Memorandum was designed to prevent. Not only that, but doubts would be cast over

all of our already existing international commitments, including those to our

NATO allies.

The common understanding of Article 5 of the NATO

Charter is that if Russia were to invade an NATO member state, all other

members of that organization would then be at war with Russia, but that isn't

necessarily the case. What Article 5

says is that in the event that one party is attacked, each of its NATO allies

"will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually

or in concert with the other Parties, such actions as it deems necessary,

including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the

North Atlantic area." This does not

compel the use of armed force, but only suggests it among those actions a party

may deem necessary. What if we deem it

not to be?

For example, Russia has put Estonian Prime Minister

Kaja Kallas on a wanted list, for her alleged crime of tearing down Soviet-era

monuments. In Estonia, that is. This has been widely dismissed as a symbolic

action, but what if it isn't? The

obvious message behind it is that the Russians believe Estonia is theirs over

which to rule. If Russia were to launch

an operation into Estonia, a NATO country, for the purpose of apprehending

Kallas, how would America respond?

If we read Article 5 the same way Dougherty reads the

Budapest Memorandum and W.C. Fields read the Bible ("looking for loopholes"),

we will notice that it does not mandate military action. Economic sanctions and diplomatic isolation

against Russia are pretty well maxed out, however, which would seem to leave

few non-military options. In our current

political climate, it wouldn't be long before somebody proposed that we "assist"

Estonia by deeming it necessary for it to turn over Kallas for trial in Russia,

in hopes that this concession would end the conflict, thereby restoring the

security of the North Atlantic area.

That

wouldn't be too different from the advice that self-described realists are now

offering about Ukraine. For that

country's own good, they say, we must encourage it to surrender territory to

Russia, and assume that Russia will be satisfied with that outcome. Part of this encouragement would be the

withholding of aid, which the Ukrainians would only use to prolong their

suffering anyway. In order to save

Ukraine from itself, the argument goes, we must pressure it into accepting

defeat. Of course, such an arrangement

would only buy Russia time to replenish itself until it was prepared to attack

again, but the assumption here is that Ukraine is a goner anyway. "Realism," don't you know. The important thing is that America will have

been extricated from the conflict.

That

wouldn't be too different from the advice that self-described realists are now

offering about Ukraine. For that

country's own good, they say, we must encourage it to surrender territory to

Russia, and assume that Russia will be satisfied with that outcome. Part of this encouragement would be the

withholding of aid, which the Ukrainians would only use to prolong their

suffering anyway. In order to save

Ukraine from itself, the argument goes, we must pressure it into accepting

defeat. Of course, such an arrangement

would only buy Russia time to replenish itself until it was prepared to attack

again, but the assumption here is that Ukraine is a goner anyway. "Realism," don't you know. The important thing is that America will have

been extricated from the conflict.

That's a heck of a message to deliver to our allies

in NATO and around the globe. First, we rally them

to our side with a rousing Prince Hal speech, and then we retire in solitude to

the tavern like Falstaff once the fighting begins. What's worse is what it says to our

adversaries, including Vladimir Putin.

Once he has seen us welch on our commitment to Ukraine, invading a NATO

member like Estonia might strike him as a brilliant tactical maneuver. If America backs down, based on the dubious

assertion that we are not pledged to defend the people of Estonia, the whole

alliance will be exposed as a perfidious fraud.

At this time, it might seem as if Russia lacks the

wherewithal to launch another invasion, but perhaps it just needs to pick its

opponents more carefully. According to

Global Firepower, a think tank that measures the relative military strength of

nations, Ukraine ranks #18 out of 145.

Estonia is #87, Lithuania #88 and Latvia #99. If we help Russia negotiate its way out of

its Ukrainian morass, surely it remains powerful enough to gobble up these far

tinier neighbors, once the inhibition imposed by the NATO alliance has been

lifted. It can always come back for

another bite out of Ukraine when it is through.

Maybe the American political opponents of Ukraine

don't see anything wrong with that.

Maybe the disintegration of NATO is part of what they've been after all

along, which appears to be an abdication of American leadership around the

world. If that's the case, then they

have a responsibility to the American people to make that argument publicly and

be willing to defend it, even if they are not pledged to do so.

The Shinbone: The Frontier of the Free Press