Posted on February 28, 2004

The Constitution

in Black and White

by

Daniel Clark

During a February 5th grilling before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Ninth Circuit Court nominee William Myers was criticized by committee Democrats for his "narrow" interpretation of the Constitution's commerce clause. Myers had taken the position that this clause did not empower the federal government to prohibit gold mining within a particular area of California.

His critics characterized this opinion as a threat to the rights of black Americans, because the commerce clause has in the past been expanded beyond its actual meaning in order to enact civil rights laws. Since he sought to impose the meaning of that clause, which empowers Congress to regulate commerce among the states, but not within a state, Democrats expressed concern that he might knock out the legal underpinnings of the desegregation movement.

As far as political demagoguery goes, this is a minor case by recent standards. It is pointed out here not due to its unfairness to Myers, but because of its insult to the U.S. Constitution. The courts' historical misinterpretations of the commerce clause, and Democrat fears that its meaning will be restored, have each played a role in perpetuating one of the biggest and most insidious lies ever told: that black Americans' rights descend from activist judges, and that therefore our Constitution is an obstacle they've needed to overcome.

Former vice president Al Gore perpetuated this fable during the 2000 presidential campaign with these remarks: "When my opponent, Gov. Bush, says he will appoint strict constructionists to the Supreme Court, I often think of the strictly constructionist meaning that was applied when the Constitution was written and how some people were considered three-fifths of a human being." This statement reflects a popular belief, and one that is probably being taught to high school and college students across America. But is it true?

A "strict constructionist" is one who interprets the Constitution to mean just what it says, and the Constitution has never said that anybody is "three-fifths of a human being." The three-fifths clause deals with the apportionment of representatives in the House. What it actually says is, "Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons." This says only that a slave represented three-fifths of a unit to be added to the formula which determines a state's congressional representation, not that slaves themselves were literally only three-fifths human.

Furthermore, it was the pro-slavery faction that wanted the slaves to be represented on a one-to-one ratio with free people, because that would have maximized the congressional representation of the Southern states. The three-fifths rule was the result of a compromise proposed by Northern abolitionists. Using Gore's logic, one would conclude that it must have been the abolitionists who were the racists. To the contrary, since the slaves themselves were not represented in Congress, this compromise actually benefited them, by reducing the political clout of their oppressors.

Not only was Gore's statement factually wrong, but the insinuation it made was entirely phony. He was clearly trying to scare black voters into believing that a faithful application of the Constitution would demote them to subhuman legal status. Even putting aside misunderstandings about the intent and the effect of the three-fifths rule (which was repealed by the Fourteenth Amendment, in 1868), one ought to at least acknowledge that it had applied only to slaves, and not to free blacks. For Gore to suggest that it loomed as a threat to black Americans in the year 2000 was fallacious, but typical of his party's strategy of fomenting interracial suspicions.

Naturally, the abolitionists would have preferred not to credit the Southern states for their slave populations at all. James Madison's notes from the Constitutional Convention indicate that there was concern that allowing slaves to count toward congressional representation would encourage the importation of more of them. Therefore, an importation tax was proposed, in an effort to curtail the growth of the slave trade. This tax appeared in Article I Section 9, as part of an apparent trade-off, the other half of which being that an outright ban on slave importation was taken off the table for the following twenty years.

Some might contend that the delay of a ban on importing slaves was itself an endorsement of slavery, but the language of the clause does not bear this out. Like the rest of the Constitution that was written at that time, it makes no mention of the word "slavery," nor does it suggest in any way that one person is capable of owning another. What it actually says is, "The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person."

The part of this clause relevant to slavery is written more generally about immigration. It cannot possibly be taken as constitutional protection for the institution of slavery, especially when confronted with an amendment, ratified concurrently, which prohibits it.

The Fifth Amendment clearly states, "No person shall ... be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law." No matter how broadly or narrowly "liberty" is interpreted, it must, at a bare minimum, mean freedom from being imprisoned on a plantation and forced to perform slave labor. If it doesn't mean that, then the word holds no practical meaning at all, and would not have even been written into the document.

Since each of the Constitution's indirect references to slaves categorizes them as "Persons," and the Fifth Amendment says no "person" shall be deprived of liberty, then a strict constructionist would have understood that the Constitution demanded the abolition of slavery. The fact that this was not done is the fault not of the Constitution, but of those responsible for interpreting and enforcing it.

The infamous judicial assault on black Americans' liberty rights that was Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) was the antithesis of strict construction. Rather, it was one of the most flagrant examples of judicial activism in American history.

Dred Scott was a slave who was taken by his master, an army doctor named John Emerson, to live for several years in Illinois, a free state, and then in the Wisconsin Territory, where Congress had banned slavery as part of the Missouri Compromise. Scott eventually returned to his native Missouri, where slavery was still legal.

After Emerson's death, Scott sued for his freedom, arguing that he'd been freed by his residence in Illinois and Wisconsin. His case was based on Article IV Section 2 of the Constitution, which says, "The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States." This would mean that Missouri had to honor the freedom that Scott had gained while living in a free state.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Roger Taney disagreed, claiming that, "A free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a 'citizen' within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States." That's a curious finding, since the Constitution did not define citizenship until passage of the Fourteenth Amendment eleven years later, and it had nothing specifically to say about people of African ancestry.

Incredibly, Taney declared that, "The Constitution of the United States recognizes slaves as property, and pledges the Federal Government to protect it." This fabrication is conspicuous even by today's standards. Since the Constitution recognized slaves as "Persons," and therefore acknowledged their right to liberty in the Fifth Amendment, it could not simultaneously consider them to be the property of others, in the context of that same amendment. Here and elsewhere in his opinion, Justice Taney simply assumed that the Constitution must approve of slavery, just because society had continued to allow it during the time since the Constitution was ratified. The thought that a constitutional right could still exist, despite having been violated for decades, seems to have been beyond his grasp.

Justice Taney furthermore declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, due to a creative interpretation of Article IV Section 3. Part of that section says, "The Congress shall have Power to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property belonging to the United States." Taney determined that this only referred to those territories that existed at the time the Constitution was written, and not to the new territories added by the Louisiana Purchase, despite the fact that the Constitution itself makes no such distinction. Therefore, the congressional prohibition of slavery in the territories north and west of Missouri was nullified.

As if that weren't enough, he interpreted the final clause of Article IV Section 2 in such a way as to make the institution of slavery transportable from slave states to free states, despite the wishes of the citizens of the latter. That clause reads, "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due."

A strict constructionist would recognize that this refers not to slavery at all, but to indentured servitude. There was no agreement between slave and master that meant that the slave's labor was "due" his master. Slaves worked because they were forced to do it, not because they were indebted. The language of this article implies a contract between two people, not ownership of one person by another.

Nevertheless, Taney ruled that this meant a slave remained the property of his master, even while residing in a free state. Whereas he had rebuked federal power over slavery laws in striking down the territorial regulations, he and six of his colleagues erroneously claimed that the federal Constitution barred states from enacting a meaningful ban on the practice.

Outrage over the Dred Scott decision spurred a group of Wisconsin abolitionists to form the Republican Party, whose first president, Abraham Lincoln, was the subject of yet another chapter of anti-constitutionalist mythology.

It has become a popular perception of Lincoln that he was something of a renegade president, who was more than willing to cast the Constitution aside in fervent pursuit of his extra-constitutional principle of preserving the Union. This impression is based on the argument that the slave states were within their rights to secede from the Union, just as they had voluntarily joined it. While that rings true to our founding concept of government by the consent of the people, it is complicated by two passages in Article I Section 10, saying that, "No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation," and "No State shall, without the Consent of Congress ... enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State."

While it would have been legal for one state to secede, it was plainly unconstitutional for a cluster of states to form an alliance and all secede together. Once this was done, Lincoln was bound by his oath of office to subdue the illegal Confederacy. Therefore, it was Lincoln's enforcement of the Constitution, and not his alleged flouting of it, that ultimately abolished slavery.

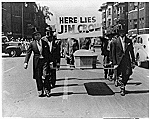

During the struggle over segregation a century later, the Constitution was again wrongly cast as a hapless bystander. The heroes of this story were the legislators and judges, who saved the day by bending the rules the way Superman bends iron bars. When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was drafted, it often employed the word "commerce" in reference to practically any instance in which money might change hands. Certainly, this is not an accurate usage, but it had been used previously in both legislative and judicial contexts, so it must have been included in the law under the presumption that the Supreme Court would accept it, which it did.

The commerce clause of Article I Section 8 grants Congress the power, "To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes. In Atlanta Motel v. United States (1964), the Court used this language to uphold the Civil Rights Act, declaring that, "The interstate movement of persons is 'commerce' which concerns more than one State."

Somewhere along the line, the Supreme Court seems to have concluded that it can make anything be true, simply by putting it in writing. "Commerce" is the large-scale trade of commodities. "The interstate movement of persons" can only qualify as "commerce" if the persons are the ones being traded. Ironically, if the Constitution had defined the word the way the Supreme Court has, the anti-constitutionalists would probably now be wailing that President Bush's judges will reduce people to the legal status of cattle.

The Court attempted to clarify this interpretation, by adding that, "The protection of interstate commerce is within the power of Congress under the Commerce Clause whether or not the transportation of persons between States is 'commercial.'" So commerce isn't necessarily commercial? That's like saying that heat isn't necessarily hot.

All the while, the Constitution provided a perfectly rational argument for banning segregation in its Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The due process clause of each of those amendments prohibits any state from depriving a person of liberty, without due process of law. One definition of "liberty," and the one that most logically applies in this context, is freedom from physical restraint. The Civil Rights Act could have been validated without distorting the Constitution, on the grounds that segregation, being a degree of confinement, was a violation of constitutional liberty rights.

It's not surprising that neither Congress nor the Supreme Court decided to go this route, when they both must have understood that the alternative would expand their powers. By prying open the commerce clause, they created a pilot hole through which to force federal intervention into virtually any state issue. This practically nullified the Tenth Amendment's demand that, "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."

Anti-constitutionalists in the federal government misinterpreted the Constitution in order to delegate to themselves powers that were not rightly theirs. Because they did this in the process of combating an injustice against blacks, they now accuse those who would uphold the Constitution of brandishing a tool of oppression.

The truth is that slavery would have been abolished decades sooner, and many of our nation's racial frictions ameliorated, if the Constitution had been enforced to the letter from the very day it was ratified. It can be pointed out that segregation was defeated all the same by an activist judiciary, but the Supreme Court's creative interpretations weren't so benevolent a hundred years earlier.

Democrats' grim fantasies about what horrors Bush's judges might inflict on the nation are easily refuted, because anyone can see what a strict constructionist really stands for. Just pick up a copy of the Constitution. It's all right there in black and white.

The real danger lies in trusting the devious imaginations of judges who take it upon themselves to create laws and distribute rights. If they can assume the ability to do that, then they have the ability -- as demonstrated in Dred Scott -- to just as capriciously take those rights away.

The Shinbone: The Frontier of the Free Press

Mailbag . Issue Index . Politimals